Being based in Berlin, I cannot help but look at the music industry every so often. It certainly doesn’t help that the Berlin Music Week is happening.

And we all should look to the music industry every so often, because a lot of battles have played or are currently playing out there that eventually spill over to other industries. Music had to deal with disbanding way before it hit the newspapers, and with monopolistic distribution infrastructures way before Amazon became a thing in eBooks. And given their greed, they’re also the folks who seem most stuck-up when it comes to “intellectual property” rights, and licensing.

I haven’t “owned” music in a long time.

Access means licensing

When I moved from Heidelberg to Berlin, I sold all the CD’s I still had. And even though I’ve invested into a good LP-player when I got to Berlin, my Vinyl collection isn’t actually shaping up at the pace I initially had hoped. Nonetheless, I consume more music than ever.

I haven’t “owned” music in a long time, because in most cases, I get a license to listen to music, rather than ownership over a physical copy of a piece of music.

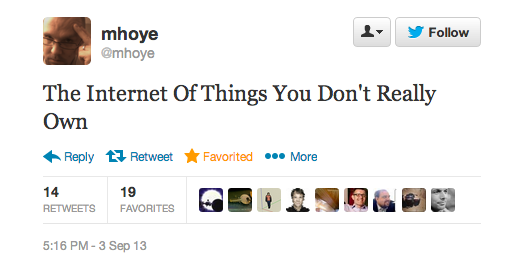

This is how we deal with what the industry likes to call “content” nowadays. We don’t own it. We own licenses to it.

This change happened, because the underlying structure changed. Instead of physical objects, music turned into data. Files on your computer. On those files on your computer, you never really own. You just have a license to store them, and to play them. So when I listen to music on my stereo, it plays on the stereo that I own, but I don’t really own the music.

Terms and Conditions may apply

Here’s an interesting thought-experiment: With the new intelligent, smart door-look, which relies on the manufacturers server infrastructure to communicate with your mobile phone to reliably establish, what happens when you run afoul some asinine provision in that service’s Terms of Service?

You own the physical product. There is a lock on your door, that you can remotely control from your smart phone. But you cannot use the service anymore, so it’s functionality, that added benefit that you originally bought it for, is essentially meaningless.

If you take, for instance, the slew of smart fitness tracking devices. Be they manufactured by Nike, Fitbit, Jawbone or Withings, they all don’t just do tracking. Their real value lies in the connection to a web service, which allows me, as a user, to track my workouts, compare that with my friends, give me aggregate analytics, etc. That use, of course, is bound by Terms of Service, and a whole slew of other legalese, and means, in essence, that I only really own a thing on my wrist. The functionality that I bought it for resides on their servers. I only have a license to use it. But should I ever run afoul of any license restrictions, that object, that fancy thing on my wrist that I paid good money for, is essentially useless. It’s a Thing I Don’t Really Own.

As A User, I Want To Own My Stuff

A while back, Amazon-users suffered an ironic incidence: Unauthorized copies for George Orwell’s 1984 had been distributed as eBooks via Amazon’s Kindle store. After the rights-holders complained to Amazon, the company decided to remove all purchased copies from any Kindle, including notes and all.

How do we ensure that the same situation doesn’t happen with the users of fitness tracking devices, smart door locks, or intelligent heating systems? One way would be to move as much smartness to the edge, that is, the devices themselves. That of course is not always practical, given the restrictions that most connected devices operate under. And it’s often not desirable, as those devices benefit from aggregate data analytics which combines the data from several units.

Another would be to force companies to service users who bought their devices. But as every purchaser of DRM-protected music from the Microsoft Zune-Store will be able to attest to, this is not a guarantee for users.

Ultimately, nothing will beat open standards and interoperable systems. Service portability – being able to control my intelligent heating system with whichever service provider I so chose – is the only meaningful solution to this. The alternative would be heavy-handed regulation or upset users. Both scenarios no vendor could currently like.